Individual Performance in a Simple Functional Ecosystem

This is a model of individual performance in a functional ecosystem. This is a very simple ecoystem, consisting of a single Actor and a “project” consisting of a small set of tasks. The point of such a simple system is to use it as a stepping stone to more complex models.

Does This Qualify as a Functional Ecosystem?

It is important to support claim that this qualifies as a functional ecosystem. The nexus of any functional ecosystem is the set of affordances and the associated semoiotics in that system and their interrelations. Those interrelations can be constitutive, informational, regulatory, or functional/operational. Here are the three criteria for an functional ecosystem:

- One or more Actors – All functional ecosystems need at least one Actor, where an “Actor” is an agent acting in a role). Otherwise there is no proper subjectivity, i.e. frames of reference to interpret/decode the sign systems and no capabilities to engage with affordances. To qualify as an Actor, the agent needs values (i.e. purposes, goals, evaluative criteria, etc.) and also semiotic capabilities (i.e. ability to engage usefully with sign systems).

- One or more affordances – All functional ecosystems need at least one affordance, otherwise the Actor would not be able to purposefully engage in the system (except possibly through automaton-like behaviors or functionally “blind” perterbations). There may be multiple objects in a system (i.e. colored balls in an urn), but also just one or a few affordances (i.e. “drawable”, “inspectable”) that all objects share.

- Interrelations must be autocatalytic – The interrelations in the system must be coherent and self-contained to a large degree. This means they must be able to function as a whole, filling in any “gaps”, and must be self-reinforcing when being constituted or in operation.

Note: This is the most subtle/powerful/conceptually challenging criteria!

This last criteria – interrelations must be autocatalytic – deserves more explanation. First let’s understand the conceptual and theoretical background of “autocatalysis”. reft:padgett_emergence_1997 and reft:padgett_emergence_2012 explain the concept in social systems by using close analogies from chemistry (where the terms “autocatalytic” and “hypercycle” originated) and and also computer systems. Regarding the later, (reft:padgett_emergence_2012, p 60, quoting Sewell: “Recursive relationships between rules (or schema) and resources, with rules transforming resources and resources reproducing rules. This is the same thing as autocatalysis…”).

Instituional Analysis and Development Frameork (IAD)

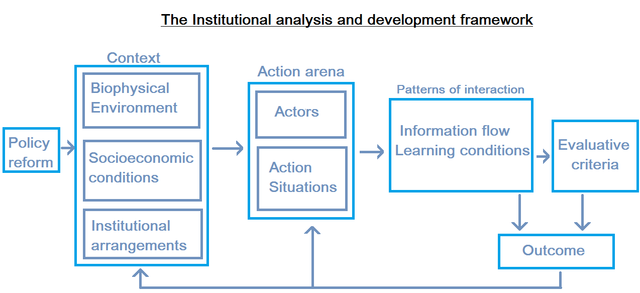

Let’s get concrete, using Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework

Ostrom defined classes of rules that map to this framework:

| Rule type | Description |

|---|---|

| Position | The number of possible “positions” actors in the action situation can assume. (In terms of formal positions these might be better described as job roles, while for informal positions these might rather be social roles of some capacity.) |

| Boundary | Characteristics participants must have in order to be able to access a particular position |

| Choice | The action capacity ascribed to a particular position |

| Aggregation | Any rules relating to how interactions between participants within the action situation accumulate to final outcomes (voting schemes etc.) |

| Information | The types and kinds of information and information channels available to participants in their respective positions |

| Payoff | The likely rewards or punishments for participating in the action situation |

| Scope | Any criteria or requirements that exist for the final outcomes from the action situation |

For any set of rules to be “autocatalytic” they must be interrelated in a self-reinforcing, self-reproducing sort of way. Consider these four rules as a system:

- Rule_1_Position ::= an agent can be a “Contoller” or “Member”, but not both

- Rule_2_Boundary ::= an agent can act as “Controller” only if it has capabilities for a) goal setting, b) monitoring, and c) corrective action.

- Rule_3_Choice ::= Member actors have the choice to “comply” or “not comply” with any decision or directive.

- Rule_4_Information ::= Directives are messages from Controllers to all or specific Members that mandate actions.

Are these four rules alone autocatalytic? The answer is: no.

First, there is no boundary rule for “Member”, even though Members are referenced in rules 1), 3) and 4). Also there is no rule defining “actions” that Members might take, as referenced in 4). Second, there is no Information rule for “decision”, even thought it is referenced in 3). Finally, there are no rules at all regarding outcomes or evaluative criteria.

If these four rules were a computer program, they would generate “compile-time errors” because of the missing function/variable definitions. They would also generate “run-time errors” because of missing outcomes and evaluative criteria – as if a program function returned no values and there was no stopping condition for the program.

Minimum Viable Autocatalytic Set

What is the minimum autocatalytic set in the IAD? I would guess it would be five rules:

- One Position rule – to define the Actor’s role

- One Boundary rule – to define the criteria to qualify as this Actor, and also to define it relative to the action situation and also the environmental context.

- One Information rule – to define the information that the Actor will take in

- One Choice rule – for one type of action the Actor might take

- One Payoff rule – that defines both outcome and evaluation

(Note that Context and Action Situation are not part of the rule set, but they do provide the necessary substrate.)

By analogy to Object-oriented computer programs (OOP), we can translate this into a single class with two methods – decide and evaluate – and a single class variable state, which has possible values of start, continue, or stop:

- Class defintion Position rule + Boundary rule

decidemethod Choice ruledecidemethod parameters Information ruledecidemethod return value Payoff ruleevaluatemethod parameters Payoff rule

It also needs two other features to be a running program: a “constructor” that instantiates the class with an initial value for state, and a exec method to put it into action. But notice that these are minimum capabilities required for any agent program, so we do not include them here.

Assuming we properly initialize this computer program in a Context and Action Situation (via a “constructor”), this program with run without compile time or run time errors, meaning there are no gaps in variable/function definitions and none of the operations return empty results (i.e. “null pointer exceptions”, “divide by zero”, etc.).

We have just demonstrated that this 5-rule set is functionally complete. If you imagine leaving out any one of the OOP elements, above, the program wouldn’t run. But is it self-reinforcing and self-producing, as the definition for autocatalysis proclaims? What does it mean to “self-reinforce” and also to “self-produce”? Here we must part company with Chemistry, because rules (and norms) are not physical entities like molecules and they don’t produce or catalyze each other in the same way.

What it Means to be “Self-reinforcing”

When two rules (or norms) “reinforce” each other, they clarify, amplify, activate, regulate, or contextualize each other. The minimum level of reinforcement is definitional and constitutional, that is, a set of rules reinforce each other minimally when they define each other without gaps. In computer lingo, this means “no complile-time errors”. Also, at minimum, a set of self-reinforcing rules support each other in action, both during rule creation or modification (i.e. constitution) and also rule execution. In computer lingo, this means “no run-time errors”.

What it Means to be “Self-reproducing”

That’s pretty clear, but the notion of “self-producing” or “self-reproducing” rules (or norms) is a bit harder to conceptualize. Here is an analogy that can help us think about this – beach sand and ocean waves (small). The ebb and flow of ocean water is analogous to social behavior, while valleys and channels in the beach sand are analogous to norms and rules that constitute institutions. Every time the ocean flows up and down a given channel, it “reproduces” it in a way – carving it by moving sand out, and adding to it by moving sand in. Let’s say there are two small sand formations near each other: 1) a circular lagoon and 2) a river-like channel. What is the “meaning” of these two formations (institutions)? In the first case, the meaning is “constrained circulation with eddys” while the second is “laminar flow in a constrained linear path”. Every time the ocean flows into these two formations, the action of the ocean reproduces the material shape that gave rise to it. Now imagine that the tide is going out and these two sand formations are exposed to sun, wind, people and animals walking, etc. They will gradually lose their shape, i.e. be “forgotten”. In this sense, they depend on the interaction of the ocean to reproduce those shapes. They are functionally interrelated.

Leaving the analogy, now consider institutions such as marriage. Everytime two people get married they “reproduce” the institution, at least to a small degree. Everytime those people are treated as married (i.e. when filing taxes, when running for political office, etc.) the institution of marriage gets “reproduced” a bit. If people stopped getting married, and if societey stopped treating married people in specific ways, then the institution of married would fade from society, even if it continued to exist in documents, language, and laws.

Here is a vital point. This type of “reproduction” is funamentally different from biological reproduction, either asexual or sexual reproduction in the case of living beings (archaea, bacteria, and eukaryote domains), or replication in the case of non-cellular life (viruses and bio-active chemical systems). This distinction is why direct analogies with biological Darwinian evolution are not appropriate for studying the evolution of instituions.

In biological reproduction or replication, there is always a single reproduction/replication event for every new individual – its birth event. (Same could be said for death events.) Everything leading up to that reproduction/replication event sets the conditions for it happening or not, and also directing who/what is “born” via mechanisms in the reproduction/replication process. The “selective retention” aspect of Darwinian evolution happens both in death processes (likelihood, longevity) and also in birth processes (retaining traits during reproduction/replication), while the “blind variation” aspect happens mostly in reproduction/replication mechanisms and events leading up to it.

But institutional reproduction is not a single event, but instead it is either continous (or nearly so), or episodic (and often repeated). The variational and selective forces are potentially at work all this time, though the detailed sequence variation and selection matter.

To Do

- One or two more paragraphs describing how the continuous or episodice mechanism of institutional innovation leads to different dynamics than Darwinian evolution.

- Move this whole section to a different chapter, and reference it here.

Actor Learning and Performance Cycle

Here is a sketch of the Actor’s cycle of learning and performances that we will be modeling.

- The Actor comes to the project endowed with a set of skills and experience that are relevant to perceived needs of the project.

- The Actor assesses the tasks and decides (consciously or unconsciously) how to approach them. This approach constitutes both the “framing” (i.e. “the story about how this project will be performed by this Actor”) and “frame” (i.e. the Actor’s ‘“cognitive schema”) that will be deployed, and also the Actor’s expectations.

- The “approach” also includes organizing the tasks into a sequence, a hierarchy, or otherwise composing or decomposing them into “chunks” of activity.

- The Actor starts working on tasks, applying the chosen routines (i.e. processes, procedures, tools, methods). The course of work is guided by making decisions in a goal-subgoal tree, and reasoning about alternative choices at each decision point.

- During the course of work, the Actor creates information through engagement with the affordances in the task environment and artifacts. This engagement includes literal or imaginary manipulation, semiotic perception and conception processes, and abduction. This information created in this way becomes instrumental in guiding further activity and for handling unforseen contingencies or exceptions.

- The “semiotic processes” here are aligned with the construct of “sensemaking”.

- There is a coevolution between the Actor’s conception of the problem space (tasks, goals, challenges) and the solution space.

- There are two types of crucial information: fulfillment of expectations and progress. If expectations are met, then the current framing and frame are reinforced. If expectations are not met, especially in surprising ways, then framing and frame are adjusted or replaced to “make sense” of the unfolding state of affairs. If progress is sufficient or better, then the current course is reinforced. If progress is insufficient, then more effort/resource may be applied, or perhaps there will be reframming.

- The Actor may start to codify and/or abstract (generalize) her knowledge about the task and task performance. This knowledge may be embedded in knowledge artifacts that become instrumental to the Actor going forward. (They are “knowledge artifacts” because they are functionally significant for the Actor to manifest and put to use the Actor’s knowledge in some specific situation.)

- An important class of knowledge artifacts are sketches, prototypes, mockups, and simulations.

- Another important class of knowledge artifacts are design documents, notes, photos, journals, instructions, etc. that recorde specifics about the task performance along the way and contribute toward the end product.

- Another important class are “proto-institutions”: norms and rules that the Actor formulates and begins to follow.

- At some point, the Actor decides that work is complete on each task, either because the results are satisfactory, the goal is reached, or some constraint has been reached (time, energy, resources, effort). (Return to Step 1 to start a new set of tasks)

Types of Ignorance and Uncertainty

Here is a list of the possible varieties of ignorance and uncertainty our Actor may encounter during the course of project work:

- Ambiguity

- Imprecision, Non-specificity, over-simplification

- Vagueness, Fuzziness

- Variability, Instability, Inconsistency, Noise

- Incommensurability

- Infeasablility

- Paradoxical (i.e. self-defeating, self-refuting)

- Error

- Misinterpretation, indecipherability, Over-interpretation

- Non-sequitor

Actors use their reasoning, action, and interaction capabilities along with the informational resources extracted from affordances in the task environment to cope with and resolve these ignorances and uncertainties. In particular, the knowledge artifacts created along the way, including “proto-institutions” are prime instruments for progressively resolving ignorance and uncertainty in order to make decisions and achieve (sub)goals.

Proto-institutions

Though we cannot say that there are institutions at work in a simple single Actor ecosystem, we can located the precursors of institutions, a.k.a. proto-institutions. These are norms and rules that the Actor creates for herself.

Habits and Conditioned Responses

These constitute reflexive reasoning inside the Actor – actions without any conscious thinking. They arise purely as a response to internal or environmental queues and situations, conditioned by past behavior and experiences. If the Actor is mistaken, and the environment does not match what is expected, then the habit or conditioned response “fails”, and the Actor needs to recover by reacting differently or doing something differently.

While it is tempting to call these “proto-institutions” because they are “taken for granted”, I believe they do not qualify. They may be the raw material, but they lack the structure, coherence, and instrumentality that we expect from institutions. They only become “visible” to the Actor in their failure. In particular, habits and conditioned responses do not reduce uncertainty or ignorance on the part of the Actor who enacts them. Quite the reverse. They depend on certainty, predictablity, and lack of surprises.

Personal Norms and Rules ⇒ Intrinsic Reward System

Personal norms and rules constitute the Actor’s intrinsic reward system – self-created, self-governed, and self-reinforced. These norms and rules function almost the same as norms and rules in multi-actor social settings, but not quite, which is what qualifies these as proto-institutions.

Of course personal norms and rules build on and extend the Actors instinctive, “inborn” reward system. But we’ll see below how they are different.

What is crucial about personal norms and rules is that the Actor holds the recipe for constituting and enacting them. This recipe is tied up in the framing and cognitive schema of the Actor, and also habits and conditioned responses (i.e. serving as “raw material”, as noted in the previous subsection). This is a vital difference between intrinsic and external rewards (and penalties). An Actor’s intrinsic reward system is interwoven in the Actor’s beliefs, and in the way the Actor thinks, sees, reacts, and behaves, including percieved options and choices available. In contrast, external rewards (and penalties) sit outside of most of this, and are always experienced as Other, constituted and controlled from the outside, and therefore not as malliable and frequently inscrutible.

Three Cannonical Intrinsic Rewards:

1) Progress, 2) Significant Surprise, and 3) Frustration

These three are not the only common or cannonical intrinsic rewards, but I believe they are both common and central to performing conceptual/informationa/abstract tasks. In other words, it vital that the Actor have some ways to gauge progress, lack of progress, signs that indicate possible changes of direction, and excess expenditure of resources. In physical tasks, these are fairly obvious and immediate for an organism in neuro-physical sensations, but in an conceptual/informationa/abstract tasks these reward signals need to be synthesized by the Actor through engagement with the task environment.

Consider the game of chess played by two intermediate players. Player A is midway through a particular chess opening and is setting a strategy for the middle game. As the game unfolds, how can Player A tell whether or not she is making progress on this strategy? There may be intermediate goal states in terms of move sequences or partial piece positions, or their may be something less specific having to do with the overall shape and tempo of the game (e.g. who has initiative).

Now what happens when Player B makes a move or two that were completely unexpected by A, and maybe moves that appear to be irrational (as A imagines B to be thinking)? This is ambigous because it could be a sign (indicator) of very different possibilities: either 1) B is making a blunder or 1) B has discovered a fatal flaw in A’s strategy and is now exploiting it through these moves that “don’t make sense” to A. If Player A does not have some intrinsic reward system for detecting and responding to significant surprises, this set of unexpected events would not receive sufficient salience or reflection.

Let’s say that Player A responds by rethinking her whole strategy, and starts thinking through completely new strategies and lines of play by both players. How much time and effort should she spend on this? How much time should she spend on rethinking lines of play that she has already considered and rejected? Especially if Player A is on the verge of believing that her original strategy and reasoning were mistaken?

At some point during this process, Player A must be able to sense the penalty of frustration, where progress in any line of analysis is exceeded by the costs in term of time and attention. Notice how a utilitarian calculation (costs vs benefits) as come into being. I believe that utilitarian formulations and calculations arise from situations and do not proceed in the background on a continuous basis to govern decisions and behavior.

Notice that in all three of these cases in the chess game, Player A was drawing information from the task environment through semiotic processes – i.e. seeing and interpreting signs, and incorporating those perceptions and interpretations in how she was thinking and planning. Also, the task enviroment (primarily the board postion) provides affordances for a variety of strategies or ploys (i.e. combinations of moves that have some near-term purpose or even “trick”, like gaining some material advantage, or “pinning” a major piece so it can’t move). Even more, the moves of Player B provide both affordances and signs that Player A might be able to utilize, depending on her skills and current position/resources.

Of course, there is reasoning in chess that is not primarily semiotic, i.e. imagining sequences of moves and counter moves, and the relative merits of positions after those sequences.